The point is, you don’t need to be a fortune teller to predict frustration, and the same thing is true for rushing.

When you think about anticipating error, especially your own, it’s an interesting concept because—obviously—if we all knew that we were going to make a mistake at exactly 3:15 p.m. every day, chances are it wouldn’t take us very long to figure out that a quarter after three was a bad time.

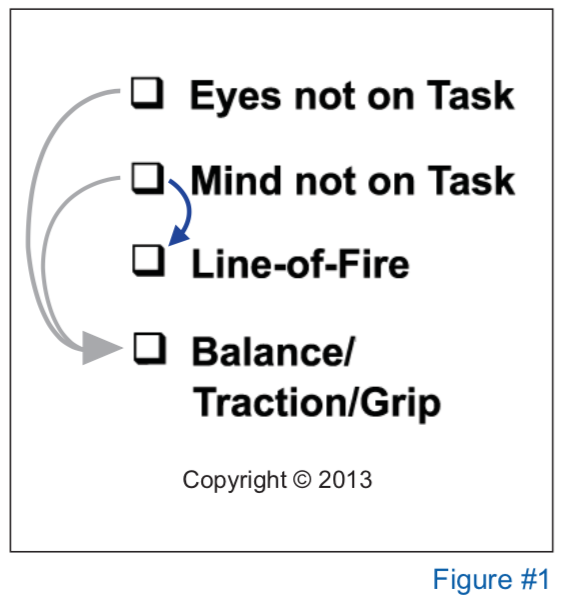

But (alas) human error is not predictable to that degree of accuracy. However, what if we asked the question a bit differently? Suppose you could win $1,000 if you could predict your next mistake. Or, to be more specific in terms of safety, suppose you could win $1,000 for predicting your next critical error (see Figure #1), or combination of critical errors: for example, eyes and mind not on task leading to a problem with balance, traction or grip, or mind not on task leading to line-of-fire.

So...what would you pick? If you’re like most people, you probably haven’t thought about when you’re going to make a mistake today, even though it’s rare that anybody can go much more than a day, let alone a week, without making at least one (or two or three) critical errors.

We might recognize the potential for making mistakes like forgetting something—especially if it’s happened before— like forgetting your wallet, passport or car keys. But what about critical errors that can get you hurt? When are you most likely going to be making one of those errors?

Well, for folks who have been through training on human factors, situational awareness or critical error reduction techniques, they would likely start thinking about when and where they would find themselves rushing, frustrated, fatigued or a bit too complacent since they (we) are usually in one or more of those states before we make a critical error.

For instance, most people can predict when they’ll likely be in a rush, at least for the next day or two. And we can normally predict when we’re going to be tired, like early mornings and late afternoon or late at night.

And finally, you can probably predict when you’re most likely going to be a bit too complacent—especially when there’s lots of hazardous energy around, like driving to and from work.

So, when you think about predicting or anticipating critical errors—it’s not impossible. It just requires that you think about your day and what you’ll be doing, and then think about the four states.

However, you need to give it a bit of thought. For instance, let’s look at frustration. Who in your world makes you frustrated: nobody, everybody or only some people—some of the time?

What makes you frustrated: everything, nothing or only some things—sometimes?

So, if you already know who or what makes you frustrated, you could “self-trigger” or think about the risk in advance; which would help to increase your awareness to the situation—if it occurs—which (in turn) will help to reduce the risk of making a critical error or a combination of critical errors.

Frustration and Rushing are Predictable

Consider the following (true) story: A father was having trouble getting his teenage son to do his homework. The boy didn’t like math. So the father tried to work with the boy to help him get his homework done. His grades were not good. The father told him that it was important that he put more effort into it. He told him that since he wasn’t a “natural,” he would just have to work a bit harder. The boy didn’t see the point. “I’ll never be really good at math,” he said, “so why bother?”

This “discussion” had been going on for weeks. Both of them were losing patience. The father knew he couldn’t give up, but it was frustrating. The boy was skillful (to say the least) at stalling or avoiding the homework. Finally, the father told him that from now on, he couldn’t go out and play with his friends or practice with the team until the homework was done. The next day was Saturday, the weekend. The boy was getting ready to go out and practice with the team, but the father said, “You can’t go out until your math is done.”

“But it’s Saturday, we’ve got practice,” the boy said.

“I don’t care. You have to get your homework done first.”

“You’re kidding...right?” the boy said incredulously.

“No, I’m not,” the father said sternly. “Your homework has to be done first. It always has to be done first.”

“OK, OK, I’ll do it,” said the boy. But he didn’t go towards his room to start.

“I’m serious,” said the father. “You can’t go out until it’s done, do you understand?”

“Yes, I understand,” the boy exclaimed. “Now shut up about it.” And he started to walk away.

Hearing his boy telling him to shut up was too much for the father. He grabbed his son by the shoulder. The boy shrugged forward to get away. Because the grip was so tight, the father’s hand didn’t let go—but his shoulder did. It went slightly out of the socket, and he couldn’t do much with his right hand for a month. His rotator cuff was slightly torn.

Could the father have “monitored” his frustration level and prevented this from happening?

Well, although being told to “shut up” was unexpected, the frustration escalating wasn’t. And having a sore shoulder

for a month didn’t likely help the boy’s geometry or algebra either...so, as usual, little good comes out of these situations.

But, let’s face it: parents having trouble with their teenagers is not uncommon. It’s very predictable. And maintenance personnel getting frustrated with production employees, or production employees getting frustrated with maintenance personnel isn’t unpredictable either. And the list goes on (and on). The point is, you don’t need to be a fortune teller to predict frustration. And the same thing is true for rushing: people with deadlines or production quotas are likely going to rush—especially if the deadline is looming or they’re behind in production that day.

Fatigue is probably the easiest of all the states to predict. As individuals we usually know when we get tired. And for people who work shifts, it’s easy enough to predict that they’re likely going to be fatigued (or very fatigued) the first day or night of the new rotation.

It’s rare that anybody can go much more than a day, let alone a week, without making at least one (or two or three) critical errors.

So, even though all mistakes are unexpected, anticipating error is easy enough—if you think about when and where you will likely be rushing, frustrated, fatigued or complacent. Granted, you won’t always know. Things do change—like traffic jams caused by a motor vehicle accident—but many things don’t.

And, if things do change from normal, chances are you will notice the change—since it’s different—and you will naturally think about whether the change is good or bad, and whether the change will cause you to rush or be frustrated, or whether fatigue will be an issue. This should help you to be able to self-trigger on these states more easily and much quicker.

Complacency, unfortunately, is much harder to recognize within yourself. However, it’s really easy to think about your day or even the upcoming week and identify tasks, jobs or activities where you know complacency leading to mind not on task and mind not on task leading to other critical errors could potentially meet with significant amounts of hazardous energy.

Just start with the bathroom or shower in the morning (lots of people get hurt in bathrooms). Then progress to the drive or however you’re getting to work (it’s very common for people to be thinking about what they have to do at work instead of thinking about driving or getting on the bus, subway, streetcar, etc.). Once you get to work and you know what you’re going to be doing, think about what tasks you can do without having to think too much, that you can do on “auto-pilot.” Asking yourself, “What could go wrong, and how bad could it be?” when you’re doing these tasks will help to remind you of the risk when you actually get to that task. Then, once you’re done work for the day, think about the drive home and what you’re going to be doing later on, and whether fatigue will also be an issue. (It’s easy to get complacent about fatigue.) If you do identify a potential problem, try thinking about how it could be worse or if it’s worth getting hurt over. This should also help you to fight complacency.

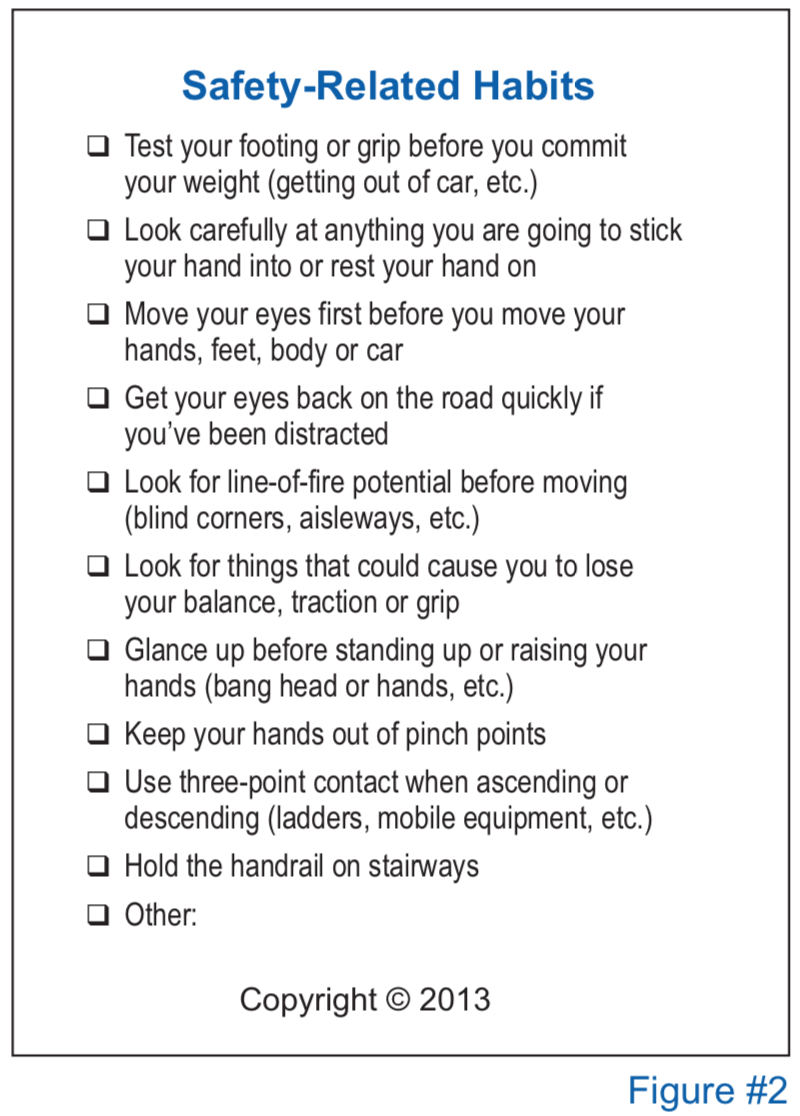

However, even if you think about when and where you’re going to be in one or more of the four states, it’s still possible—fairly likely in fact—that your mind will go off task here and there, which is why it’s important to think about what safety-related habits you need to work on so that what you do automatically is safer. This could be anything from three-point contact when ascending or descending to moving your eyes first—before you move your hands, feet, body or car (see Figure #2).

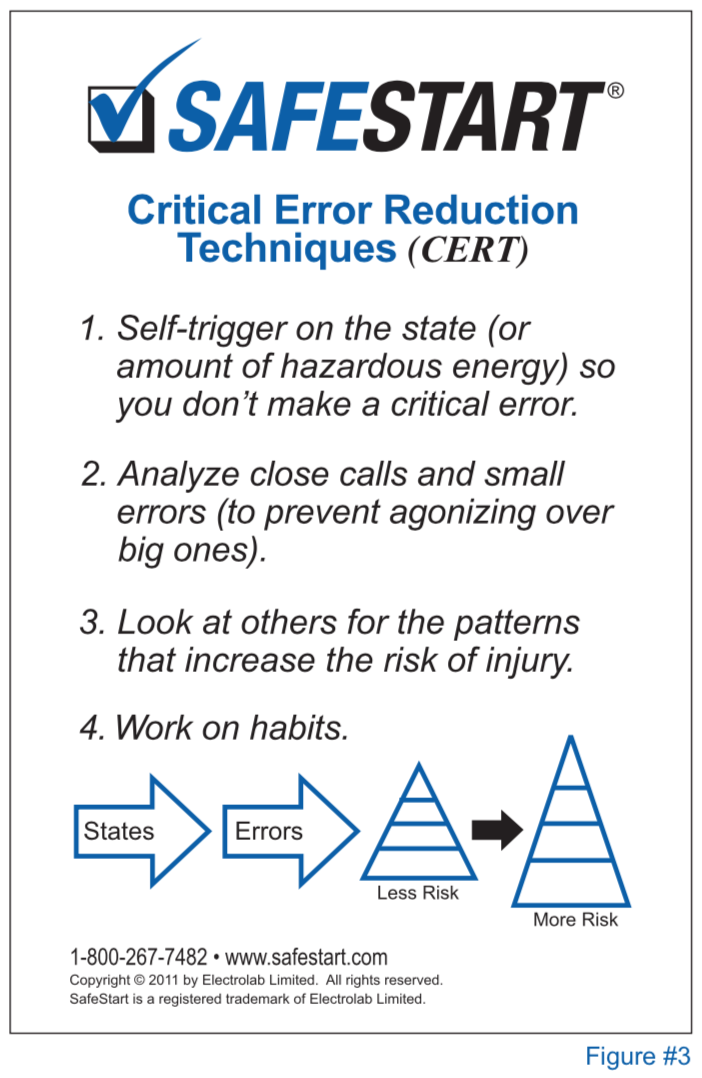

The critical error reduction technique of “look at others for the patterns that increase risk of injury” (see Figure #3) will

also help you to anticipate the errors other people could make. But it will also help you to fight complacency leading to mind not on task because when you see risk or increased risk, it tends to make you think about your safety and the risk of what you’re doing at the moment.

However, waiting until someone else makes a critical error might not give you enough time to get out of the way or out of the line-of-fire. But if you notice that they’re rushing or see signs of frustration, fatigue or complacency, then you can anticipate when they will be more likely to make a critical error, which will give you more time to react or stay out of harm’s way.

For example, if you see someone driving and looking at a map, you can anticipate that they might make a sudden turn, drift over the shoulder or center line, slow down, not use their turn indicators or stop and ask for directions.

OK, now suppose you see someone driving while trying to eat a sandwich or hamburger. You could anticipate that they might miss their mouth or take too big of a bite and spill some of it or drop some of it in their lap. If they tried to clean it up while they’re still driving you could anticipate that they might not be looking at the road or thinking about driving safely, which means that they might easily drift over the line or onto the shoulder.

And finally, suppose you see someone weaving a bit and having trouble staying in the center of the lane on a long stretch of highway. What states and critical errors could you anticipate? Well... most likely it’s a sign of fatigue combined with complacency, which means they could easily move into the line-of-fire if they have one of those “long blinks” and start to drift.

So, provided we pay attention to what’s going on around us, we can even anticipate the critical errors other people could make.

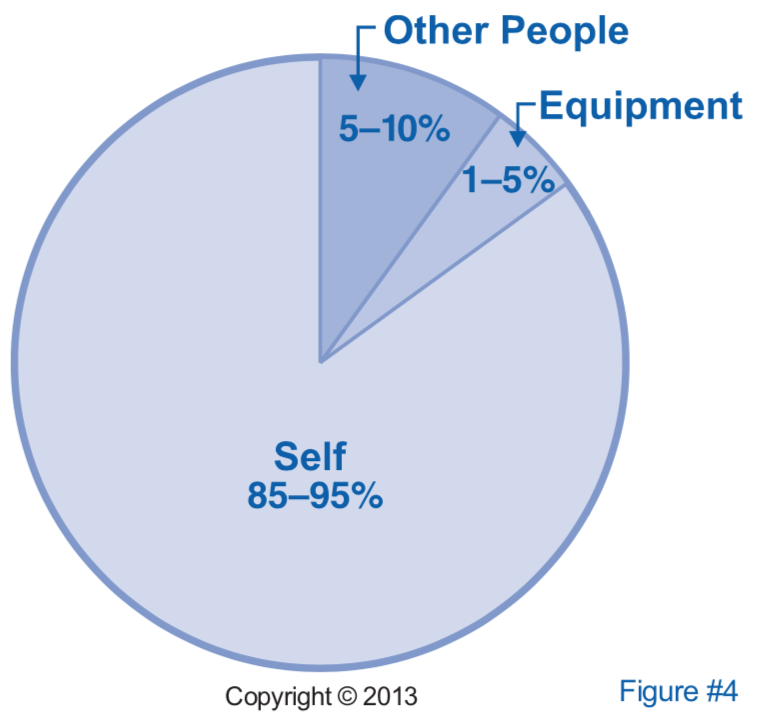

However, the other guy making mistakes and getting us hurt hasn’t been a big problem for most of us—compared to making critical errors ourselves (see Figure #4).

Where will you make that $1,000 mistake?

But it’s not hopeless. Even though we will all still continue to make mistakes (nobody will ever be perfect), that doesn’t mean we can’t anticipate when and where we’ll be the most likely to make serious critical errors and prevent them. We just have to give it a bit of thought in advance. Just ask yourself, “If I could win $1,000 for predicting my next (big) problem in terms of critical errors and hazardous energy: When and where would it happen? What would I most likely be doing?”

Granted, nobody’s going to give you $1,000 if you’re right. But some critical errors or combinations of critical errors like falling asleep at the wheel can cost you your life, which— for most people—is worth more than $1,000 and worth taking a few seconds for...

Ironically, the more you think about when and where you’ll make that $1,000 mistake, what does that do to your chance of actually making that mistake and winning the $1,000?

So, it’s really pretty straightforward. But you do have to give it a bit of thought—in advance: Just ask yourself, “Where and when (in my life) will rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency meet with significant amounts of hazardous energy?”