Using Critical Error Reduction Techniques

Although it’s common knowledge that “good safety is good business”, most of the claims are for indirect benefits in terms of quality improvement and production improvements. Typically, the argument is that if you lose a good worker due to an injury, then production will suffer and so will quality because the good worker would need to be replaced with an inexperienced worker who won’t be as fast or as good—at least not right away.

However, these are indirect benefits. There was never a claim that the safety program would directly improve production or quality; or for that matter, that it would improve customer service, HR, finance or administration.

And although critical error reduction techniques focus on injury causing errors (arguably, the most important category), they also prevent non-injury causing errors; because as mentioned before—nobody’s ever trying to make any mistakes—period.

So, by teaching employees critical error reduction techniques, not only will it help prevent someone from losing their balance, traction or grip in the first place but it will also help keep them from making quality mistakes if they happen to be in a rush or if they were overly tired. The critical error reduction techniques will also help prevent errors due to frustration or complacency, which could also cause quality problems or production problems or maintenance problems.

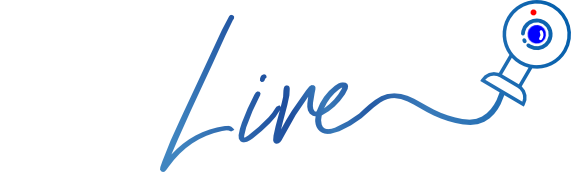

So, what are critical errors and what are critical error reduction techniques? Critical errors are those errors that are involved in over 95% of all accidental injuries. There are four of them:

1. Eyes not on task

2. Mind not on task

3. Moving into or being in the line-of-fire

4. Problems with balance, traction or grip

One of the reasons for this is that most safety devices (seat belts, fall arrest systems, etc.) do not prevent the error or incident from happening. They just mitigate the outcome so that the damage/injury is less severe. In other words, the seat belt never prevented a car crash in the first place. It just kept you from breaking your neck going through the windshield. Similarly, the fall arrest harness and lanyard never stopped anybody from losing their balance, traction or grip in the first place either, but it did do a good job of keeping people from falling to their deaths.

So yes, if we lost our best welder due to a serious injury, production and quality will suffer, but we aren’t saying that our traditional safety efforts are actually going to make him or her a better welder. No matter how good he or she is, they will still— nevertheless—make mistakes. Even the most highly trained and experienced surgeons, scientists and tradesmen make mistakes. Some of those mistakes could lead to injury, some could lead to a defective weld or, in some cases, some of these errors could simply lead to a delay or slower production.

All of these errors would, by definition, be unintentional, which means that regardless of the outcome—the person, tradesperson, scientist or surgeon didn’t want or mean for it to happen. Conversely, if they’d prevented the error in the first place—then none of the problems would have happened.

We have to look at what causes all errors

However, simply focusing on the errors won’t be enough to prevent them, which is why there has been so much attention given towards mitigating the error or the consequences of the error (seat belt, fall arrest harness, etc.).

In order to prevent making critical errors, we have to look at what causes all errors because we can’t be selective about what kinds of errors we make. We all know that no one was ever trying to get seriously hurt, but we also all know that no one was ever trying to make any mistakes—big or small—either.

So now what we need to look at is what causes people to make mistakes, or at least, what causes people to make the most mistakes. And again, as hinted at before, rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency cause over 95% of human error. Granted, there are also states or human factors like extreme joy, extreme sorrow or panic that can easily cause people to make mistakes. However, those states aren’t very common; it’s not Christmas every day, you’re not going to a funeral every day and thankfully, we’re not running out of burning buildings every day. But the four states of rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency are very common. Most people find themselves in one or more of these four states every day.

So if you look at these four states, the first three are active (or different than normal). You can tell when you’re in a rush or going faster than what’s normal for you and you can tell when you’re angry or more angry than normal, same for fatigue.

So as soon as you recognize that you’re in one of these first three states, you need to quickly think about not making one or more of the critical errors. In other words, you need to trigger on the rushing or “self-trigger on the state.”

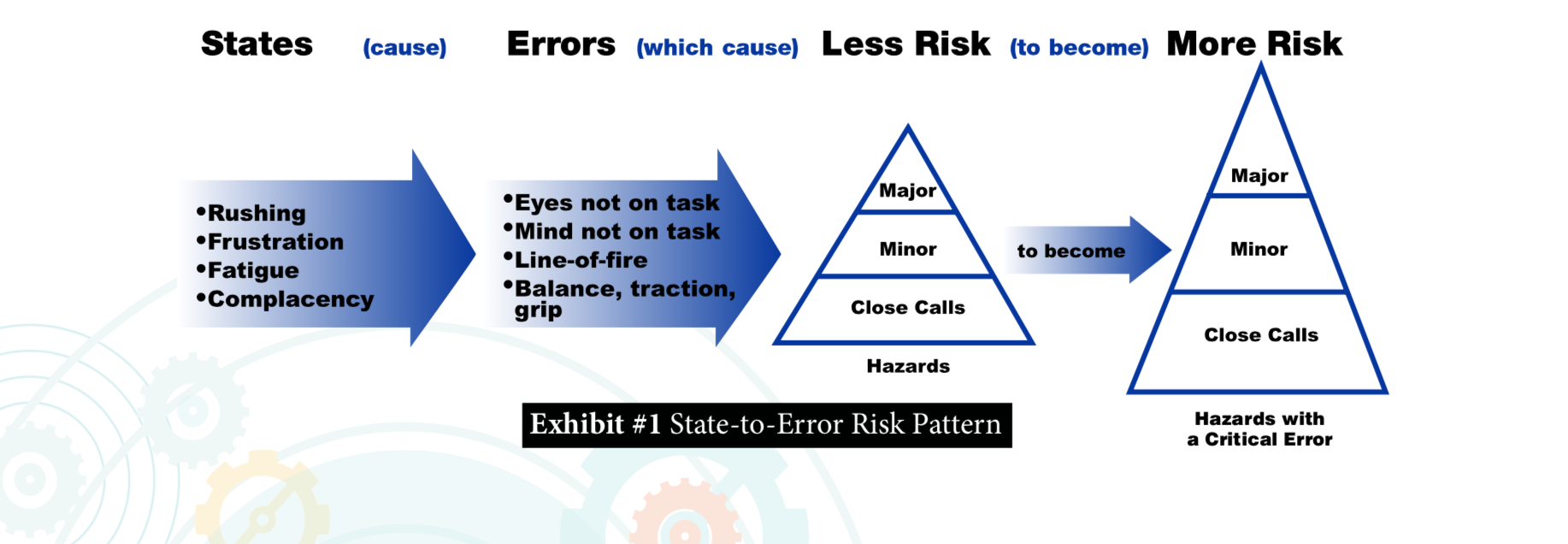

And that is the first critical error reduction technique. Unfortunately, complacency is a passive state which means that there isn’t anything abnormal or different that you can trigger on. Complacency can easily lead to mind not on task once the risk/skill required is no longer pre-occupying. If you’re not thinking about what you’re doing, then your behavior will be what you do normally or automatically or habitually, so in order to compensate for complacency leading to mind not on task, we need to get people to work on their safety-related habits (see Exhibit #2), like moving your eyes first before you move your hands, feet, body or car.

The next critical error reduction technique is designed to fight complacency or to help bring your mind back on task, whereas working on your safety-related habits only compensates for mind not on task. However, if you observe people for the state-to-error risk pattern—and you see it—it will almost automatically make you think about what you’re doing—right now.

For example, suppose you see someone on the freeway and they’re following way too close to the car in front of them. Once you see this, you’ll immediately check your own following distance, which is different than if you get in the habit of leaving a safe following distance, which will only help to compensate if your mind goes off task and you stay driving on auto-pilot.

So working on your habits helps to compensate for complacency, and looking at others for the state-to-error risk pattern helps to bring your mind back to the moment, or helps to fight complacency.

The last critical error reduction technique (see Exhibit #3) is to analyze close calls (instead of just agonizing over the big ones).

So, even if it’s something as small as a momentary loss of balance, instead of just saying, “That’s weird, I don’t normally stumble on the stairs...” think about it. Was it a state like rushing, frustration or fatigue that you didn’t self-trigger on, or, if it was complacency leading to mind not on task, then it’s probably a safety-related habit that needs more work or you need to make more of an effort to observe others for state to error risk patterns.

Once your employees know and understand the critical error reduction techniques, they can use them to prevent any mistake—injury causing or not—that was caused by rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency or a combination of them.

So, the final question is how many quality mistakes, production mistakes or maintenance errors are also caused by rushing, frustration, fatigue or complacency? We’ve all heard the expression, “Haste makes waste” but what about complacency? Well, one example that comes to mind happened at an oriented strand-board mill about ten years ago. We were walking from the maintenance shop back to the front parking lot. It was 5:00 p.m. That’s when the day shift maintenance employees finish. As we were walking by the compressor room, one of the millwrights stopped and listened. The other maintenance employee also stopped. The first one said, “You hear that?” The second one said, “Yeah, sounds like the bearing.” Then the first mechanic looked at his watch and said, “It’ll probably be all right until morning...” to which the second said, “Yeah, let’s look at it tomorrow.”

Long story short, the press went down at 4:00 a.m. and they lost $84,000 worth of production. So, do you think fatigue and/or complacency were contributing factors? If they had heard the noise earlier in the day, or if the noise was a bit louder—do you think they would have just walked away?

And this is just one of many examples where production and quality suffered because of one or more of the four states. But there are also lots of examples and case studies where companies that have trained their employees in critical error reduction techniques have improved quality and production.

One was a large automotive assembly plant with 4,600 employees. They reduced on the job injuries (recordables) by 67%. They reduced off the job injuries by 70% and they saved 2.3 million dollars in first run defects.

Another example is a large equipment manufacturer that reduced scrap and rework by 30%. There are even examples of hockey teams and basketball teams that have won championships three years in a row... and the list goes on and on.

The whole idea of directly improving performance by eliminating the error vs. just mitigating the error is new to safety, and wasn’t really possible with protective devices and engineering controls. The idea of making your good workers better vs. just not losing them to injury wasn’t an available option—the technology/methodology didn’t exist. So people just focused on the indirect benefits. However, teaching your employees critical error reduction techniques will directly improve safety, quality and performance regardless of the type of industry you’re involved in.